Singlet oxygen, an electronically excited form of molecular oxygen, is an important signaling molecule that has a significant hormetic effect, making exposure to it in low levels highly beneficial to one’s health and longevity.

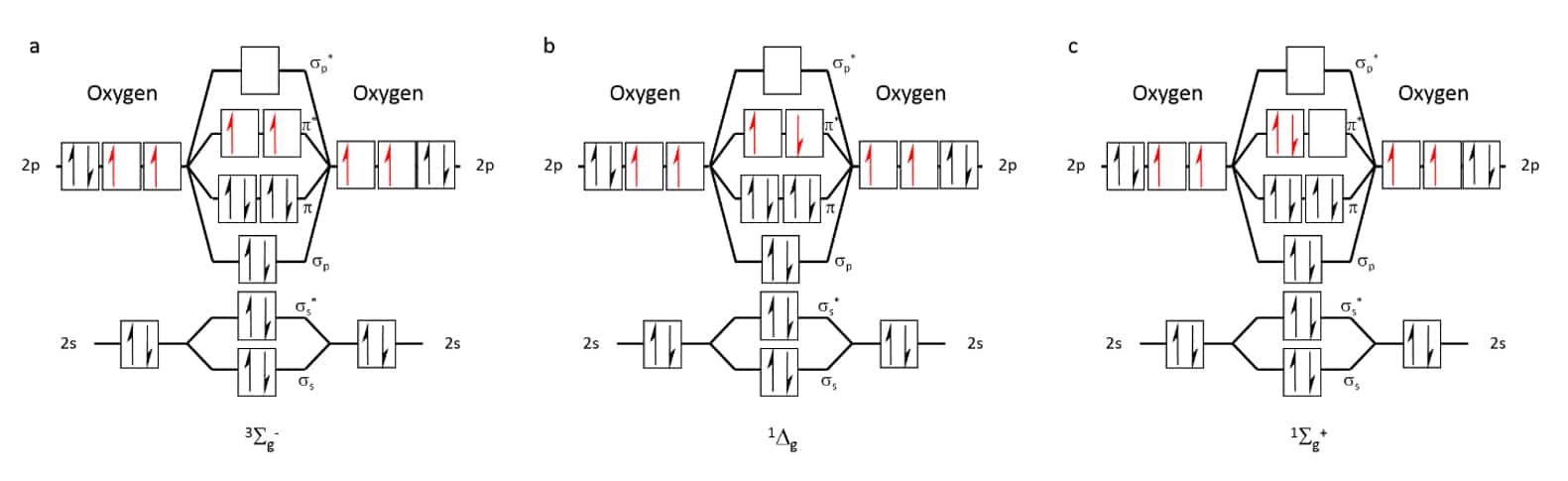

Oxygen makes up about 20% percent of the air and is essential to life. Oxygen is most found in the atmosphere as the dioxygen molecule, O2, that is a diradical, as its lowest electronic state is a triplet (3Σg–) state in which two unpaired electrons are distributed in the two highest occupied degenerate orbitals (Figure 1-a). Oxygen in the triplet state (3O2) is not very reactive due to spin restrictions, as most other molecules are in the singlet state, though it will readily react with radicals that are in the doublet state. However, excitation of the molecule will result in the rearrangement of the electron spins and the orbital occupancy to form two possible singlet electronic states, 1Δg and 1Σg+ (Figure 1b and c, respectively), who are highly reactive. The 1Σg+ state oxygen is very reactive and has a relatively short lifetime as it tends to quickly relax to the lower energy 1Δg state. Therefore, the 1Δg singlet state, that is only 23 kcal above that of the ground state,[1] is the state involved in most oxygen reactions that do not involve radicals and is the state that is referred to when discussing singlet oxygen (1O2). The transition between the singlet to the triplet state is considered to be forbidden, and as a result is highly improbable. As a result, the lifetime of an isolated singlet oxygen in the gas phase is relatively long- 72 minutes.[2] This time gets shorter the higher the probability of a collision, meaning the higher the pressure and/or temperature, the lower is the singlet oxygen’s lifetime. In the gas phase, the lifetime can drop to mere seconds, depending on the conditions.[3] In solvents, however, the lifetime gets even shorter, dropping to microseconds or even nanoseconds.[4]

Figure 1 Occupation of molecular orbitals in oxygen at different energetic states: (a) triplet ground state, 3Sg–, (b) Most stable singlet state, 1Δg, (c) Highest energy, short- lived singlet state, 1Σg+.

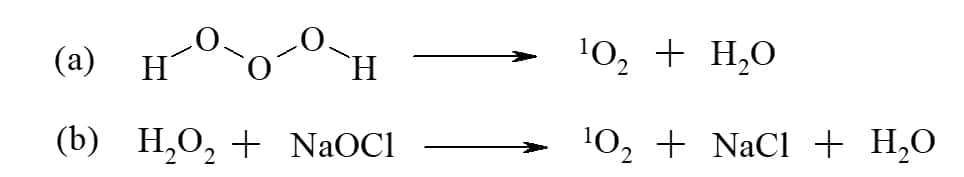

Singlet oxygen can be artificially produced by various methods, the most common of which are chemical reactions (Figure 2)[5] or irradiation in the presence of an organic dye, a photosensitizer.[6] The fluorescent sensitizer in the presence of oxygen is quenched through a radiation-less path in which energy is transferred to the oxygen, exciting it to its singlet state (Figure 3). Artificial photosensitizers are used, amongst other, for the production of singlet oxygen for medical applications such as skin[7] and cancer[8] treatment, and industrial applications such as water treatment[9]. In these applications, photosensitizers are used to create high concentrations of singlet oxygen, which cause damage to various biomolecules, thus, inducing the death of malignant cells.

Figure 2 Examples for chemical reactions to produce singlet oxygen, 1O2: (a) decomposition of trioxidane in water; (b) reaction of hydrogen peroxide with sodium hypochlorite.

Figure 3 Energy diagram illustrating singlet oxygen (1O2) that is generated from ground state triplet oxygen (3O2) via energy transfer from the excited state of a photosensitizer to the oxygen molecule upon irradiation.

As was mentioned above, the common methods used for singlet oxygen production are mostly applicable in solutions or require an oxygen-enriched gaseous environment. In order to produce singlet oxygen in atmospheric air, an immobilized photosensitizer is usually used. However, photosensitizers tend to degrade over time, losing their effectiveness as a result of photobleaching by singlet oxygen or by some other process. In addition, the yield of the immobilized photosensitizers is lower than that of the unbound molecules. As a result, devices based on immobilized photosensitizers display reduced yield and have limited life span.[10]

ZMedicAir has patented[11] a groundbreaking technology that provides a unique non-irradiative metal-based method for producing singlet oxygen-enriched air. This is the first time ever that a free singlet oxygen has been shown to be produced due to interaction of flowing air over metals. Metal oxidation commonly occurs through the interaction of molecular oxygen with metals. In this process, singlet oxygen production is assumed to occur as the oxygen atoms in the metal oxide are in the singlet state, while molecular oxygen is in the triplet state, as mentioned above. This means that a spin flip of the oxygen to its singlet state had to have occurred as part of the oxidation process. However, since the spin flip of the oxygen quickly leads to the oxygen atoms’ disassociation and, subsequently, to the metal’s oxidation,[12] singlet oxygen formed in this process has never been isolated and identified until now.

In our invention, adsorbed excited oxygen molecules readily disassociate from the metal surface due to the force exerted be the air flow. This effect is possible providing that the metal-oxygen interaction is weak enough. The yield of the free singlet oxygen produced changes depending on the metal used, as the interaction between the metal and the incident oxygen needs to be strong enough to enable its excitation to the singlet state, but weak enough to enable the dissociation of the singlet oxygen from the metal surface before it continues to react. By using alloys of various relevant metals at different ratios we can further fine tune the singlet oxygen yield. The singlet oxygen in the ZMedicAir device is produced in the air in low levels.

Singlet oxygen formation through photo-excitation can also occur naturally by natural pigments.[13] For instance, the chlorophyll molecule, that is the green pigment in leaves that plays an essential role in photosynthesis, can act as a photosensitizer (Figure 4), especially at high light intensity, in which case the singlet oxygen acts as a signaling molecule as it leads to photoinhibition, thus protecting the photosynthetic mechanism from the intense light.[14]

Figure 4 Scheme showing energy transfer events in photosystem II, part of the photosynthetic mechanism in chloroplasts in plant green cells that can result in singlet oxygen formation.14 * marks excited states. Pheo, pheophytin; QA, plastoquinone A

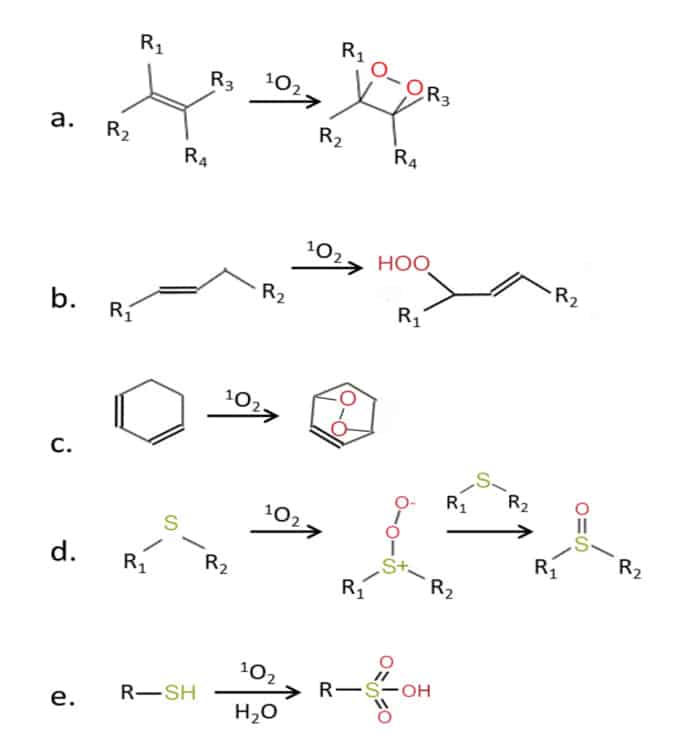

More importantly, it has also been shown that singlet oxygen is produced in plants and animals is various enzymatic processes. In animals, singlet oxygen can be formed in various compartments of somatic cells, such as in peroxisomes, in the endoplasmic reticulum, in the cytosol, and most significantly, in the mitochondria.[15] Mitochondria are cellular organelles that produce energy (ATP) through aerobic cellular respiration, during which oxygen is used as an electron source. Side products of this process are various reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (OH·), superoxide anion radical (O2·−) and singlet oxygen (1O2). This constant formation of singlet oxygen within the body leads to a constant base line concentration of singlet oxygen within the organism, that in neutral conditions is estimated to be around 10−13 M, a concentration far lower than what is considered to be cell damaging concentrations, that would be a concentration of about 10−8 M that is estimated to cause cell membrane damage, while a local concentration of about 10−5–10−4 M was estimated to lead to cell death.[16] This damage to the cells and tissues is incurred through singlet oxygen oxidizing different important biomolecules containing double bonds and thiol groups (Figure 5), like pigments (chlorophyl, hemoglobin…), proteins (enzymes, structural proteins, transport proteins, receptors…),[17] lipids (membrane phospholipids), and DNA .[18] When the concentration of oxidative species rises to harmful concentrations, that state is defined as “oxidative stress”.

Figure 5 Chemical activity of singlet oxygen with molecules containing double bonds (a-c), and with molecules containing thiol groups (d-e). R, R1–R4—side chain.14,[19]

Every biological system, from single cells to an entire multi-celled organism, require specific internal conditions in order to function in an optimal manner; these conditions being: stable specific temperature, pH, mineral and biomolecules concentrations and so on, known as ‘homeostasis’. However, as the outer and the inner environment of said biological systems are ever changing, specific mechanisms have evolved to help maintain homeostasis. For example, the specific concentrations of various ions within the body’s cells are maintained through a complex balance of a network of ion channels and pumps. Another example is the regulation of the body’s temperature at a very specific value, through a careful balance between the internal body heat and the external conditions through various mechanisms controlling the muscles, glands and blood flow to the skin.

When an organism fails to maintain homeostasis, meaning when the organism’s intrinsic mechanisms are incapable of maintaining stable internal conditions, it can be said that the system is in “stress”. Such failure will invariably lead to reduced function of various biological systems, and over time, to permanent structural and functional damage, as various biomolecules and biostructures incur chemical and physical damage, resulting in various diseases and syndromes. As most organisms live in changing and volatile environments, the induction of stress is certain. As a result, in order to survive and thrive, an organism has to develop mechanisms that will enable it to combat stress and return to homeostasis.

Oxidative stress is a common form of stress most organisms experience, especially organisms that rely on aerobic cellular respiration. Oxidative stress stems from a rise in the levels of various oxidative species beyond the capacity of the base line anti-oxidant mechanisms to neutralize them. As a result, biological systems run the danger of incurring oxidative damage, as various important biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids and DNA, might undergo redox reactions that will change their chemical and structural properties; a process that in many cases will render them ineffectual at best, or harmful at worst. (Figure 5).

Since high concentrations of ROS will cause damage to the cells and tissues, it’s essential to prevent ROS from reaching harmful levels. To that end, low levels of various ROS will induce cellular stress-response mechanisms[20] that include antioxidant mechanisms, as well as “healing” mechanisms to “fix” damage that the system has already incurred. The triggering of these cellular processes means that various ROS, including singlet oxygen, essentially act as a signaling molecules within the body.

Singlet oxygen has been shown to act as a signaling molecule both in plants[21] and mammalian cells.20 The signaling occurs through the chemical modification of specific biomolecules, a modification that either activates or inactivates them, thus triggering or inhibiting processes that the modified molecule is involved in. Essentially, the affected biomolecules act as singlet oxygen sensor.

The primary oxidative stress sensor that is activated by singlet oxygen is Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2),[22] which plays a crucial role in regulating the antioxidant defence system. Through the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway, singlet oxygen induces the transcription of genes that help neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and maintain cellular redox balance.

These processes can be directly connected to dealing with oxidative damage, such as enzymatic processes involved in dealing with DNA, lipid or protein oxidative damage. In addition to that, in recent years there have been more and more studies indicating on the involvement of singlet oxygen acting as a signaling molecule in various other essential processes in the body, such as the modulation of the immune system[25] and the function of various immune cells.[26] It has also been shown that singlet oxygen is involved in the regulation of neuronal development and function,[27] which led to research into the development of therapeutics through singlet oxygen for various neuronal diseases.[28] Singlet oxygen has also shown various beneficial effects, assuming that it was due to Singlet Oxygen Energy (SOE), emitted as the singlet oxygen molecule, produced in the air using photosensitizers, relaxes back to triplet oxygen.[29] However, more and more evidence is accumulating suggesting that singlet oxygen beneficial effect in the body is actually through its hormetic effect.

As mentioned above, singlet oxygen is known to be one of the Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that are produced as side product of cellular respiration that are oxidants, and as such, at high levels singlet oxygen can be harmful.[30] However, at low to intermediate concentration singlet oxygen functions as a signaling molecule, as in recent years it has become clearer that at those levels, singlet oxygen plays an essential role in the regulation of the body’s functions through the induction of low level oxidative stress.[31] This results in a form of stress-response hormesis,[32] which is a term referring to beneficial effects of a treatment that at high levels is actually harmful.[33] This effect stems from low level activation of the intrinsic cellular ROS defense mechanisms, that deal with oxidative stress, in addition to increasing the activity of phase II response enzymes that protect from damage beyond the ROS. As a result, low ROS levels lead to stress resistance, which manifests itself as reduced damage to tissues and slower aging, and, ultimately, to an extended life span.[34] At the cellular level, ROS will induce mechanisms that regulate growth, programmed cell death, and other cellular signaling. At the systematic level, they contribute to complex functions such as blood pressure regulation, improved cognitive function, calibration of the immune response and prevention of degenerative and chronic diseases,30 as the mentioned mechanisms play a very important part in the function of the immune system, that is responsible for the protection of the body from external pathogens and internal harmful processes such as cancer, and also plays a role in healing processes that occur in the body. Reduced functionality of the immune system may result in various diseases, while its faulty function may result in auto-immune diseases[35] and “cytokine storms”,[36] in which the immune system “overreacts” to various stimuli and ends up damaging healthy tissue. For example, it has been shown that exposure to singlet oxygen-enriched air reduces the level of ROS produced by monocytes as part of their defense mechanism against bacteria, cancer cells and other harmful elements. Monocytes are white blood cells that are involved in the inflammatory reaction in the body. The high levels of ROS produced during an inflammatory reaction have been shown to cause excessive tissue damage. Therefore, the reduction of the ROS levels will mitigate said damage.[37]

In conclusion, ROS need to be maintained within a certain range in the body, since not only will ROS levels that are too high interfere with the body’s functions in such a way that potentially can lead to diseases and even to death, but also ROS levels that are too low will have a similar detrimental effect.

These hormetic effects have been generally shown for various ROS, with singlet oxygen being especially effective inducer, as, in plants, singlet oxygen has been shown to be a stronger inducer of the cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, compared to other ROS such as superoxide or peroxide.[38]

The immune system’s role in conveying the ZMedicAir’s effect to the body

It has been shown that it is mainly the cell membrane through which singlet oxygen exerts its influence.[39] When reaching the outer surfaces of the body, various biomolecules on the membrane of the cells “sense” the singlet oxygen and act as receptors for it as they trigger a cascade of reactions within the cells, ultimately inducing or repressing the expression of genes that are part of oxidative stress cellular response mechanisms.[40] This response can be induced locally in the epidermis of the skin and scalp, the sclera, that is the outer layer of the eye, the epithelial layer of the respiratory system, as well as the outer most parts of the reproductive system, if exposed. This adaptation to oxidative stress is temporary, where three “waves” of signaling pathway changes were detected in research done on mammalian fibroblasts: at 0-4 hr following ROS exposure, 4-8hr and 8-12hr. [41]

An important aspect of this oxidative stress response is its induction in immune cells located in the outer surfaces of the body, such as macrophages in the lungs[42] and in the eyes[43], as part as the body’s defense from external threats.

Macrophages in the lungs play a crucial role in responding to oxidative stress, which occurs when there is an imbalance between the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the ability of the body to neutralize them. In the context of oxidative stress in the lungs, macrophages utilize several mechanisms to counteract its effects and maintain tissue homeostasis. One mechanism directly combats oxidative stress, as macrophages produce and release antioxidant enzymes, which help neutralize ROS and protect cells from oxidative damage. In addition, to that macrophages engulf and remove damaged cells affected oxidative stress, which helps prevent the accumulation of harmful substances and promotes tissue repair. In addition, macrophages contribute to tissue repair and remodeling processes by secreting growth factors that boost epithelial proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that facilitate the breakdown and remodeling of damaged extracellular matrix components.[44]

As oxidative stress can also generate pro-inflammatory signals,[45] macrophages help modulate the inflammatory response by producing anti-inflammatory cytokines to counterbalance the pro-inflammatory signals. They also release cytokines and chemokines that recruit other immune cells, such as T cells and B cells, to the site of injury to help regulate the adaptive immune response and maintain immune tolerance, and contribute to the restoration of tissue homeostasis. [46]

Macrophages have the ability to migrate to various locations within the body in response to different stimuli.[47] In response to systemic inflammatory signals or during certain pathological conditions, lung macrophages may enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body. Circulating macrophages can home to sites of inflammation or injury and participate in immune responses. may migrate to the bone marrow where they contribute to the regulation of hematopoiesis (the process of blood cell formation). Lung macrophages may also contribute to the maintenance of resident tissue macrophage populations in various organs and tissues, including the spleen, liver, and peritoneal cavity.[48]

The migration of lung macrophages to different locations within the body is tightly regulated by various factors, including chemokines, cytokines, and signaling molecules that govern immune cell trafficking and homing.48 This migratory capacity allows lung macrophages to participate in immune surveillance, host defense, tissue repair, and the regulation of inflammatory responses throughout the body This effect explains the reports on a rise in red blood cells count in people suffering from anemia, including anemia induced by cancer treatment, by ZMedicAir users.

Conditions successfully treated Using Singlet Oxygen-Enriched Air

One of the first effects that ZMedicAir users, healthy or sick, have reported is a dramatic improvement in their sleep quality. Sleep is vital for maintaining overall health and well-being, as it supports a range of physiological and cognitive functions. Getting enough high-quality sleep is crucial for a strong immune system, as sleep deprivation can weaken immune defenses, making the body more vulnerable to infections. Additionally, insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, and stroke. Poor sleep quality can also impair cognitive function, mental health, weight management, and the body’s ability to heal from injury or illness.[49] In healthy individuals, various factors such as stress and anxiety,[50] overstimulation, and poor sleep habits or conditions can adversely impact sleep quality and the ability to fall asleep. Sleep deprivation can induce oxidative stress by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and decreasing the body’s antioxidant defenses.43,[51] This imbalance leads to cellular damage, particularly in brain regions responsible for cognitive[52] and emotional functions. Moreover, sleep deprivation triggers an inflammatory response, marked by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. This inflammatory state is not only a consequence of oxidative stress but also contributes to further oxidative damage, creating a vicious cycle. Chronic sleep deprivation exacerbates this cycle, which can lead to various health issues, including impaired cognitive performance, mood disturbances,[53] and increased risk for chronic diseases like cardiovascular disorders and neurodegenerative conditions.[54]

Within just a day of use, ZMedicAir users have reported falling asleep more quickly, experiencing deeper sleep, and waking up less frequently during the night. This immediate positive effect is likely due to the hormetic effect of singlet oxygen, as mild oxidative stress may assist the body in better regulating circadian rhythms,[55] stress responses, immune functions[56] and help to maintain optimal brain function,[57] all of which influence sleep quality.

Snoring and sleep disorders are more prevalent than many realize, with over 40% of the population experiencing them at some point in their lives with varying severity. These conditions often prevent people from experiencing continuous sleep. As a result, individuals with these disorders often struggle to reach the deep sleep stage. This disruption impairs the body’s recovery processes during deep sleep.

Snoring is a common and involuntary noise that occurs during sleep when the flow of air through the mouth and nose is partially blocked. It results in the vibration of the tissues in the throat, leading to the distinctive sound of snoring. The obstruction can be caused by various factors, such as relaxed throat muscles, excess throat tissue, nasal congestion, or the position of the tongue. It is believed to afflict up to 50% of the population in varying severity and causes, so its effect can range from a mere annoyance for the snorer’s spouse to a serious physical condition, such as obstructive sleep apnea and asthma.[58] There have been more than 90 cases in which users, that used the device to treat their own specific condition, have reported on their spouse not snoring anymore as a result. One example was an asthma patient who reported that his wife, that regularly snored but was healthy otherwise, has stopped snoring because of him using the device during the night. In the case of simple snoring, this beneficial effect probably stems from improved muscle tone in the airways, as it has been shown that hormetic effect enhances muscle tone,[59] reducing the likelihood of airway collapse during sleep, thus minimizing snoring.

We also see alleviation of snoring even when it is caused by more serious conditions, like inflammation or Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). Inflammation of the airway, often caused by conditions like allergic rhinitis or sinus congestion, can lead to narrowing of the airway and contribute to snoring. The hormetic effect can stimulate the body’s natural defense mechanisms, reduce inflammation, and thereby improve airflow through the nose and throat, reducing snoring. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), which is a significant cause of snoring, involves repetitive episodes of airway collapse during sleep, which leads to intermittent hypoxia (low oxygen) and subsequent oxidative stress. The oxidative stress caused by intermittent hypoxia in OSA patients worsens tissue damage and inflammation in the upper airways, potentially increasing snoring severity. Being exposed to low levels of singlet oxygen produced the ZMedicAir device induces the body’s intrinsic antioxidant and healing mechanisms, thus enabling it to battle the oxidative stress induced by the condition in addition to healing the damage the body has already incurred.

Another reported effect of the ZMedicAir device is a significant reduction in phlegm production. Phlegm, also known as mucus or sputum, is a thick fluid produced by the respiratory system to defend against irritants and pathogens.[60] While normal in small amounts, excessive or abnormal phlegm production can pose serious health risks, including:[61] airway obstruction, hypoxemia (low oxygen levels), and infections like bronchitis or pneumonia. It can also lead to lung collapse (atelectasis) and, in severe cases, life-threatening respiratory failure. Additionally, in conditions like COPD and asthma, excess phlegm can worsen symptoms and trigger flare-ups.

While there are effective treatments for managing excess phlegm, each has its own limitations, including side effects, limited effectiveness for certain conditions, and issues with patient compliance or cost. Many treatments focus on relieving symptoms rather than addressing the root cause of mucus overproduction, which means long-term management or combination therapies may be necessary for chronic conditions. While the exact number of people suffering from chronic excess phlegm varies based on the condition, a significant portion of the global population is affected. People with COPD, chronic bronchitis, asthma, bronchiectasis, and smokers are the most likely to experience chronic phlegm, with millions of individuals globally reporting this symptom.

ZMedicAir has proven highly effective in significantly reducing excess phlegm, as many users suffering from various conditions and diseases have reported improvements in this symptom. Numerous ZMedicAir users with asthma[62], COPD[63], pneumonia[64], allergies[65], and other conditions[66] have shared experiences of substantial reductions in phlegm buildup. Additionally, heavy smokers[67] have reported the discharge of black phlegm after using the device for some time, leading to immediate relief in their breathing, as well as reduced coughing and phlegm production.

Excess phlegm not only affects patients but also impacts their caregivers, especially when the patients are children or disabled. One such case involved a young man who suffered a severe brain injury in a car accident when he was in his twenties, leaving him completely incapacitated and reliant on his mother for all his needs, even 10 years later. One of the side effects of his condition was excess phlegm, which required frequent suctioning throughout the night to prevent choking. His mother had to sleep beside him to monitor his breathing and wake up every few hours to clear his airways when he started wheezing or coughing. This constant interruption made it difficult for both the patient and his mother to get restful sleep, affecting his recovery and greatly straining his mother’s well-being. After starting to use the ZMedicAir device, within a few days, the mother noticed a dramatic reduction in the number of suctioning sessions needed at night, eventually leading to no suctioning being required at all. This resulted in significant improvements in both the patient’s and the mother’s sleep quality. The mother was able to sleep in her own room again, greatly enhancing her overall quality of life. This case also supports the effectiveness of the device, as the patient, due to his mental impairment, was unaware of the device’s use, ruling out the possibility of a placebo effect, yet still showed marked improvement.

This significant reduction in excess phlegm due to ZMedicAir use stems from the triggering of hormetic responses in the body by low levels of singlet. The activation of antioxidant defenses results in the reduction of oxidative damage and inflammation of the respiratory tract, helping to decrease irritation of the airways and overproduction of mucus.[68] In addition, through mild stimulation of the immune system, singlet oxygen may help the body more efficiently deal with infections or inflammation that lead to mucus buildup, potentially decreasing phlegm production. Another related effect is the stimulation of Mucociliary Clearance as singlet oxygen exposure could help enhance the cilia’s ability to move mucus out of the airways.[69] Cilia are tiny hair-like structures that line the respiratory tract and help clear mucus and debris. Mild oxidative stress might promote cellular repair and functioning of the cilia, aiding in the removal of excess mucus. In addition, by acting on cellular processes involved in mucus production, exposure to low levels of singlet oxygen leads to thinner, less sticky mucus that is easier to clear from the lungs, reducing the overall buildup of phlegm.

Anemia is a condition in which a person suffers from low levels of red blood cells or hemoglobin, that carry oxygen to all the tissues and systems in the body. Since oxygen is the fuel allowing the continuous energy production in the cells, reduced oxygen supply causes significant impairing of body tissues and systems. According to the World Health Organization, in 2019 around 25% of world’s population is affected by anemia (more than 1.5 billion people), when the highest prevalence is in pre-schoolers (close to 50%).[70]

The second most prevalent type of anemia, after iron deficiency, is anemia of chronic disease (also called anemia of inflammation). This type of anemia is caused by various chronic diseases such as infections, autoimmune diseases, cancer, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The anemia that results from the primary disease, may inhibit the body’s ability to combat the disease and to heal.

Using ZMedicAir has been shown to improve blood counts in anemic patients. One example involves an elderly man, estimated to be between 86 and 89 years old, who had been receiving medical treatment for dementia, heart issues, and thyroid problems for five years. Additionally, he suffered from severe anemia, with hemoglobin levels below 8 grams per deciliter. His son acquired the ZMedicAir device for him, and within two months of use, a follow-up blood test revealed a rise in hemoglobin to 10, and six months later, it increased to 10.2—a level he had not reached in three years. Notably, his thyroid and kidney functions also showed marked improvement. This case further supports that the benefits are not a placebo effect, as the patient, due to his dementia, was unaware of the device’s use.

This beneficial effect stems from the singlet oxygen-enriched air, produced by the ZMedicAir device, inducing the body’s natural ability to combat the disease’s inhibition on production of red blood cells, thus alleviating the anemia that person experiences by stimulating erythropoiesis, improving iron metabolism,[71] enhancing antioxidant defenses,23, and promoting cellular resilience[72]. Mild oxidative stress, such as low levels of singlet oxygen, can activate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathways, which are sensitive to oxygen and redox status. HIF is a key regulator of erythropoiesis (the production of red blood cells), as it stimulates the production of erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that promotes red blood cell production in the bone marrow.[73] In addition, Singlet oxygen exposure may impact iron metabolism by influencing the function of enzymes that regulate iron homeostasis. Ferritin, an iron storage protein, can be regulated by mild oxidative stress, ensuring that iron is available for the production of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecule in red blood cells.[74]

Chemotherapy is currently one of the most common and effective treatments for many types of cancer, used in approximately 50-60% of cancer cases at some stage of treatment. Its widespread use highlights its effectiveness across various cancer types and stages. However, chemotherapy is often accompanied by significant side effects, including nausea, hair loss, depression, and anemia. These side effects can become so severe that they may prevent patients from completing their treatment, putting their lives at risk. Therefore, reducing these side effects is crucial to improving cancer patients’ survival chances.

It has been shown that breathing low levels of singlet oxygen alleviates the severity of the various side effects, thus improving the prognosis and quality of life for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Low levels of Singlet oxygen have been shown to trigger the body’s natural recovery and healing processes, strengthening the body and enhancing its ability to deal with both the treatments and the tumor. Several cases have shown that cancer patients who developed anemia due to their treatment experienced significant improvement after beginning to use ZMedicAir. One such case involved a 50-year-old terminal lymphoma patient who suffered from various treatment side effects, including anemia, weakness, exhaustion, difficulty breathing, and depression. After receiving the ZMedicAir device, the patient began speaking again about an hour later, following three days of silence due to depression. Within a few hours, he reported feeling noticeably more energetic and alert. In a follow-up blood test a month later, his hemoglobin level increased from 11.2 to 12.6 grams per deciliter. Additionally, during his subsequent cancer treatment, the usual immediate side effects—such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue—were dramatically reduced.

Low levels of singlet oxygen help mitigate chemotherapy side effects by inducing a hormetic response, where mild oxidative stress triggers beneficial cellular adaptations. Singlet oxygen offers many advantages in the cancer treatment process, including the activation of antioxidant defenses, [75] which reduces oxidative damage and supports cellular health during chemotherapy. It also induces immune modulation, leading to improved immune resilience and a reduction in chronic inflammation, 25 counteracting the immune suppression often caused by chemotherapy and enhancing overall patient recovery and well-being.

The hermetic response induced by low level singlet oxygen can further reduce inflammation as it includes stimulating anti-inflammatory pathways,[76] potentially alleviating chemotherapy-related inflammation and pain. Additionally, it enhances cellular repair mechanisms, [77] strengthening the body’s ability to repair tissues and recover more effectively from chemotherapy-induced damage. Singlet oxygen may also improve mood and energy by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis[78] and energy production, which eases fatigue and boost mood, common side effects of chemotherapy.

Furthermore, it supports activation of erythropoiesis73 and improved iron utilization71, helping the body counteract chemotherapy’s impact on blood cell production, thus alleviating treatment-induced anemia. Collectively, these effects can help patients tolerate chemotherapy better, potentially reducing the severity of side effects and enabling them to complete their treatment regimen.

Asthma is a chronic, non-infectious respiratory condition characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, leading to breathing difficulties and/or coughing. It is a type of allergic disease in which the immune system “malfunctions” and reacts negatively to typically harmless external antigens, such as dust, pollen, animal dander, or even exercise. These triggers can induce an asthma attack, marked by the narrowing of the bronchi. During an attack, the bronchial muscles contract, fluids are released into the airway lumen, and edema develops in the bronchial walls. This bronchial narrowing restricts airflow, reducing the lungs’ gas exchange rate, which causes shortness of breath. The severity of this symptom is directly related to the degree of bronchial constriction.[79]

Frequent asthma attacks increase the risk of permanent bronchial narrowing. Patients may also face repeated hospitalizations, leading to missed work or school, sleep disturbances, a higher risk of obesity due to limited physical activity, chronic coughing, and an elevated risk of depression. Children with asthma are at risk for stunted growth and may have a higher likelihood of developing learning difficulties. Asthma is typically managed with a range of medications, including steroids, used both as preventative measures and to treat active attacks.[80] However, many of these medications come with side effects, some of which can be severe. Therefore, the drive to develop new treatments for asthma centers on reducing the frequency of attacks, ideally preventing them naturally, and minimizing the reliance on synthetic drugs.

Exposure to singlet oxygen-enriched air has demonstrated both immediate and long-term benefits for asthma patients. Breathing this enriched air provides quick relief for those experiencing breathing difficulties. Over time, the frequency and severity of asthma attacks have been significantly reduced, leading to a decreased reliance on medications and steroids. Patients who previously needed preventative drugs, particularly during seasonal changes, have reported no longer requiring medication after treatment. Additionally, damage accumulated from years of asthma attacks has shown notable improvement.

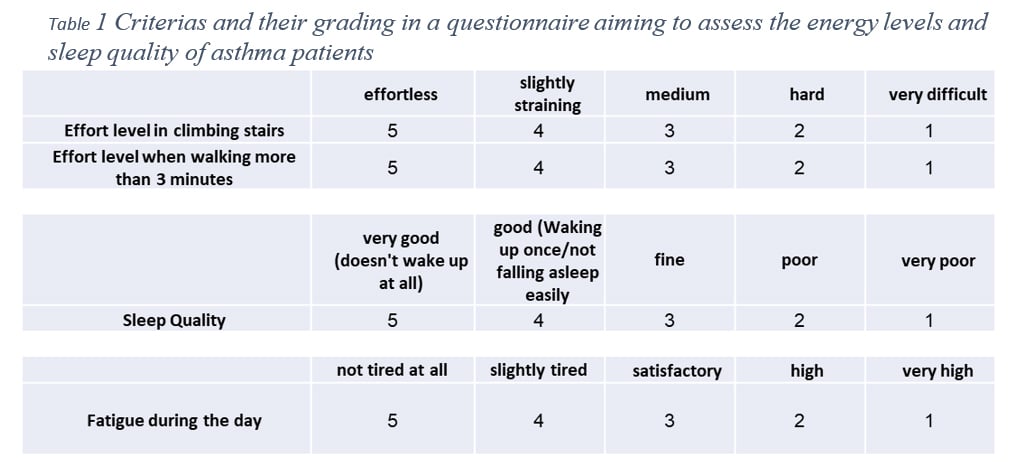

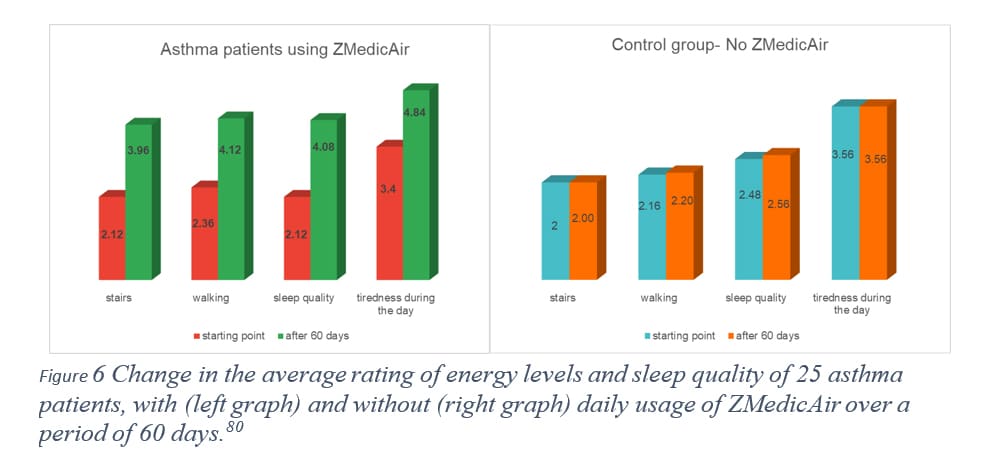

In a study conducted in Spain by Professor M. Fegricio, [81] two groups of 25 asthma patients (both men and women) were monitored for changes in their general condition over 30 and 60 days. One group used the ZMedicAir device throughout the day, while the control group received a similar device without the patented feature. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire assessing their physical condition and energy levels (Table 1). They also reported the types of treatment they used during the study period—such as inhalation therapy, inhalers, pills, a combination of inhalation and inhalers, or none at all—and noted the average number of asthma attacks per week. Figure 6 presents the average questionnaire results over the 60-day period, clearly showing a significant improvement in energy levels and sleep quality among patients using ZMedicAir, while the control group showed almost no change. Furthermore, after 60 days, 16 asthma patients in the ZMedicAir group discontinued all forms of treatment as their weekly asthma attacks dropped significantly (from an average of 1.08 per week to 0.48 per week), while the control group saw no change.

These preliminary results highlight the great benefit asthma patients can derive from a daily dose of low-level singlet oxygen.

COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a life-threatening condition that progressively impairs lung function, reducing the lungs’ capacity to absorb oxygen. COPD encompasses two primary conditions: emphysema and chronic bronchitis:

COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States, [82] with no cure currently available. Medical treatment to date can only slow the progression of the disease rather than reverse it. As a degenerative condition, COPD leads to a continual decline in lung capacity, eventually rendering patients completely reliant on supplemental oxygen and unable to leave their homes. Without a lung transplant, the condition ultimately proves fatal. Until the ZMedicAir device.

Patients exposed to singlet oxygen-enriched air reported noticeable improvements within days of use. Most of the patients treated were in the late stages of the disease, being incapable of doing the simplest of tasks like walking and talking for long. The shortest exertion resulted in low oxygen blood saturation, requiring frequent oxygen supplementation. This condition severely impacted their quality of life, leaving them mostly stationary, unable to work, and unable to travel.

After only a few days of singlet oxygen use, patients reported easier breathing and the ability to exert themselves for longer periods without needing supplemental oxygen. Within weeks, many returned to work and resumed traveling. Spirometry tests conducted after a month showed a significant increase in lung capacity—an unprecedented effect—indicating that the improvements were due to actual lung tissue recovery from singlet oxygen exposure. No other non-invasive treatment currently achieves similar results.

Healthcare costs- Asthma and COPD

In addition to the significant impact on quality of life for individuals with chronic diseases like asthma and COPD, these conditions also impose a substantial financial burden. An analysis by Duan and colleagues[83] found that the total cost of treating respiratory diseases in the U.S. reached $170.8 billion. Asthma was the costliest condition, followed by COPD. For asthma, prescription medications accounted for the largest expense at 48.0%, while for COPD, inpatient services made up 28.8% of costs, closely followed by prescription drugs at 28.5%.

Notably, the majority of COPD spending pertained to individuals aged 45 and older, whereas asthma expenditures were distributed evenly across all age groups. Private payers covered just over half of asthma spending (51.5%), whereas public insurers shouldered almost 70% of the expenses associated with COPD.

These numbers highlight the great benefit that patients suffering from these condition will derive from an alternative treatment that will improve their condition through the induction of natural healing and defense mechanisms intrinsic to their body.

Pneumonia is a widespread illness, affecting around half a billion people each year and causing approximately 4 million deaths, accounting for 7% of global fatalities each year. It is the leading infectious cause of death in children worldwide, responsible for 16% of all deaths in children under five. Pneumonia occurs globally but is especially prevalent in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where poor living conditions and limited access to medical care contribute to higher rates. [84]

If left untreated, pneumonia can lead to severe complications and even death, with children and the elderly being the most vulnerable. Treating pneumonia is challenging due to difficulties in diagnosis and identifying its exact cause, as it can be hard to determine whether the infection is bacterial or viral. Consequently, misdiagnosis and mistreatment are common. Additionally, an increasing number of drug-resistant strains of pneumonia-causing bacteria have emerged, making antibiotic treatments ineffective in many cases.

Pneumonia patients exposed to singlet oxygen-enriched air have reported immediate relief, with easier breathing and increased energy levels. Within one to three days of use, patients noted significant improvements across all symptoms, including reduced coughing and phlegm, as well as eased chest and muscle pain. Most notably, the recovery period from pneumonia, which typically lasts several weeks, was significantly shortened. Future research will explore how this solution could potentially reduce the need for traditional medicinal treatments when used in combination.

Biological basis for ZMedicAir beneficial effect for respiratory diseases

The beneficial effects for respiratory diseases of low levels of singlet oxygen, produced by the ZMedicAir device, arise from multiple mechanisms involving mild oxidative stress and the hormetic response. This treatment approach provides significant relief through several key effects:

First, it reduces inflammation by activating antioxidant defenses that neutralize excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby decreasing inflammation in the airways[85]—essential for managing symptoms and alleviating chest pain. Additionally, singlet oxygen exposure modulates immune function, enhancing immune resilience and reducing hypersensitivity. [86] This can help the body clear bacterial or viral infections more effectively, reducing the duration of pneumonia. In addition, in asthma and various viral lung diseases, the immune system often overreacts, leading to airway inflammation and constriction; mild oxidative stress helps regulate these immune responses, potentially reducing asthma attacks and improving lung function.

Singlet oxygen also promotes improved airway function by supporting the repair and health of airway epithelial cells, 84 which enhances the structural integrity of the airways, help shorten the overall recovery time and restore lung function more quickly. This also supports mucociliary clearance,68,69 removing mucus and allergens from the respiratory tract, lowering the risk of blockages and exacerbations. Furthermore, it aids in regulating smooth muscle tone in the airways, [87] helping to relax the muscles and reduce bronchoconstriction, a common feature of both asthma and COPD[88].

Finally, the mild oxidative stress response triggered by singlet oxygen activates various cellular defense mechanisms, bolstering the body’s ability to manage oxidative stress. This prevents damage to airway tissues and helps maintain optimal respiratory function, reducing the impact of asthma triggers and offering lasting benefits for patients. [89]

In summary, breathing singlet Oxygen-enriched air induces the activation of natural defense and healing mechanisms in the body, which leads to heightened neural functions, faster recovery of damaged tissues, reduced susceptibility to disease and injury, and, ultimately, increased longevity.

[1] Schweitzer, C., & Schmidt, R. (2003). Physical mechanisms of generation and deactivation of singlet oxygen. Chemical Reviews, 103(5), 1685-1758.

[2] Wilkinson, F., Helman, W. P., & Ross, A. B. (1995). Rate constants for the decay and reactions of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. An expanded and revised compilation. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 24(2), 663-677.

[3] Hasegawa, K., Yamada, K., Sasase, R., Miyazaki, R., Kikuchi, A., & Yagi, M. (2008). Direct measurements of absolute concentration and lifetime of singlet oxygen in the gas phase by electron paramagnetic resonance. Chemical Physics Letters, 457(4-6), 312-314.

[4] Hurst, J. R., McDonald, J. D., & Schuster, G. B. (1982). Lifetime of singlet oxygen in solution directly determined by laser spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 104(7), 2065-2067.

[5] (a) Noronha-Dutra, A. A., Epperlein, M. M., & Woolf, N. (1993). Reaction of nitric oxide with hydrogen peroxide to produce potentially cytotoxic singlet oxygen as a model for nitric oxide-mediated killing. FEBS letters, 321(1), 59-62. (b) Kanofsky, J. R. (1984). Singlet oxygen production by chloroperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-halide systems. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 259(9), 5596-5600. (c) Foote, C. S., Wexler, S., Ando, W., & Higgins, R. (1968). Chemistry of singlet oxygen. IV. Oxygenations with hypochlorite-hydrogen peroxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 90(4), 975-981. (d) Stephenson, L. M., & McClure, D. E. (1973). Mechanisms in phosphite ozonide decomposition to phosphate esters and singlet oxygen. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 95(9), 3074-3076.

[6] Barry Halliwell; John MC. (1982) Free Radical in Biology and Medicine. Second Edition. Clarwndon Press. OxFord.

[7] Singh, S., & Awasthi, R. (2023). Breakthroughs and bottlenecks of psoriasis therapy: Emerging trends and advances in lipid based nano-drug delivery platforms for dermal and transdermal drug delivery. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 104548.

[8] Makuch, S., Dróżdż, M., Makarec, A., Ziółkowski, P., & Woźniak, M. (2022). An Update on Photodynamic Therapy of Psoriasis—Current Strategies and Nanotechnology as a Future Perspective. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(17), 9845.

[9] Youssef, Z., Arnoux, P., Colombeau, L., Toufaily, J., Hamieh, T., Frochot, C., & Roques-Carmes, T. (2018). Comparison of two procedures for the design of dye-sensitized nanoparticles targeting photocatalytic water purification under solar and visible light. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 356, 177-192.

[10] DeRosa, M. C., & Crutchley, R. J. (2002). Photosensitized singlet oxygen and its applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 233, 351-371.

[11] Badash, Z. (2021). U.S. Patent No. 11,007,129. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

[12] Carbogno, C., Groß, A., Meyer, J., & Reuter, K. (2013). O2 Adsorption Dynamics at Metal Surfaces: Non-Adiabatic Effects, Dissociation and Dissipation. In Dynamics of Gas-Surface Interactions (pp. 389-419). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

[13] Devasagayam, T., & Kamat, J. P. (2002). Biological significance of singlet oxygen.

[14] Dmitrieva, V. A., Tyutereva, E. V., & Voitsekhovskaja, O. V. (2020). Singlet oxygen in plants: Generation, detection, and signaling roles. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(9), 3237.

[15] Sun, Y., Lu, Y., Saredy, J., Wang, X., Drummer IV, C., Shao, Y., … & Yang, X. (2020). ROS systems are a new integrated network for sensing homeostasis and alarming stresses in organelle metabolic processes. Redox biology, 37, 101696.

[16] Szechyńska-Hebda, M., Ghalami, R. Z., Kamran, M., Van Breusegem, F., & Karpiński, S. (2022). To Be or Not to Be? Are Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidants, and Stress Signalling Universal Determinants of Life or Death? Cells, 11(24), 4105.

[17] Davies, M. J. (2004). Reactive species formed on proteins exposed to singlet oxygen. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 3, 17-25.

[18] (a) Di Mascio, P., Martinez, G. R., Miyamoto, S., Ronsein, G. E., Medeiros, M. H., & Cadet, J. (2019). Singlet molecular oxygen reactions with nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins. Chemical reviews, 119(3), 2043-2086. (b) Juan, C. A., Pérez de la Lastra, J. M., Plou, F. J., & Pérez-Lebeña, E. (2021). The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(9), 4642.

[19] Triantaphylidès, C., & Havaux, M. (2009). Singlet oxygen in plants: production, detoxification and signaling. Trends in plant science, 14(4), 219-228.

[20] Klotz, L. O., Kröncke, K. D., & Sies, H. (2003). Singlet oxygen-induced signaling effects in mammalian cells. Photochemical & photobiological sciences, 2(2), 88-94.

[21] Dmitrieva, V. A., Tyutereva, E. V., & Voitsekhovskaja, O. V. (2020). Singlet Oxygen in Plants: Generation, Detection, and Signaling Roles. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(9), 3237.

[22] Kobayashi, A., Kang, M. I., Okawa, H., Ohtsuji, M., Zenke, Y., Chiba, T., & Yamamoto, M. (2004). Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 24(16), 7130-7139.

[23] Hayes, J. D., & Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. (2014). The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 39(4), 199-218.

[24] Wondrak, G. T., Cervantes-Laurean, D., Jacobson, E. L., & Jacobson, M. K. (2003). Cellular responses to oxidative stress induced by singlet oxygen: Implications for aging and human disease. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 124(8-9), 1297-1310.

[25] Ogawa, H., Azuma, M., Umeno, A., Shimizu, M., Murotomi, K., Yoshida, Y., … & Tsuneyama, K. (2022). Singlet oxygen-derived nerve growth factor exacerbates airway hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of asthma with mixed inflammation. Allergology International, 71(3), 395-404.

[26] (a) Stief, T. W. (2003). The physiology and pharmacology of singlet oxygen. Medical Hypotheses, 60(4), 567-572. (b) Nishinaka, Y., Arai, T., Adachi, S., Takaori-Kondo, A., & Yamashita, K. (2011). Singlet oxygen is essential for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 413(1), 75-79.

[27] (a) Oswald, M. C., Garnham, N., Sweeney, S. T., & Landgraf, M. (2018). Regulation of neuronal development and function by ROS. FEBS letters, 592(5), 679-691. (b) Sokolovski, S. G., Rafailov, E. U., Abramov, A. Y., & Angelova, P. R. (2021). Singlet oxygen stimulates mitochondrial bioenergetics in brain cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 163, 306-313.

[28] (a) Sheik Mohideen, S., Yamasaki, Y., Omata, Y., Tsuda, L., & Yoshiike, Y. (2015). Nontoxic singlet oxygen generator as a therapeutic candidate for treating tauopathies. Scientific reports, 5(1), 10821. (b) Wu, C. Y., Chen, H. J., Wu, Y. C., Tsai, S. W., Liu, Y. H., Bhattacharya, U., … & Kong, K. V. (2023). Highly Efficient Singlet Oxygen Generation by BODIPY–Ruthenium (II) Complexes for Promoting Neurite Outgrowth and Suppressing Tau Protein Aggregation. Inorganic Chemistry, 62(3), 1102-1112.

[29] (a) Lindgård, A., Lundberg, J., Rakotonirainy, O., Elander, A., & Soussi, B. (2003). Preservation of rat skeletal muscle energy metabolism by illumination. Life sciences, 72(23), 2649-2658. (b) Schjelderup, V., Stadheim, O., & Thorkildsen, S. Treatment of Asthma in Children with Light Acupuncture Containing Singlet Oxygen Energy.

[30] (a) Brieger, K., Schiavone, S., Miller Jr, F. J., & Krause, K. H. (2012). Reactive oxygen species: from health to disease. Swiss medical weekly, 142, w13659. (b) Rahman, T., Hosen, I., Islam, M. T., & Shekhar, H. U. (2012). Oxidative stress and human health. Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology, 3(07), 997.

[31] D’Autréaux, B., & Toledano, M. B. (2007). ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 8(10), 813-824.

[32] Gems, D., & Partridge, L. (2008). Stress-response hormesis and aging:“that which does not kill us makes us stronger”. Cell metabolism, 7(3), 200-203.

[33] Southam, C. M., & Ehrlich, J. (1943). Decay resistance and physical characteristics of wood. Journal of Forestry, 41(9), 666-673.

[34] (a) Ristow, M., & Zarse, K. (2010). How increased oxidative stress promotes longevity and metabolic health: The concept of mitochondrial hormesis (mitohormesis). Experimental gerontology, 45(6), 410-418. (b) Calabrese, E. J., Osakabe, N., Di Paola, R., Siracusa, R., Fusco, R., D’Amico, R., … & Calabrese, V. (2023). Hormesis defines the limits of lifespan. Ageing research reviews, 102074.

[35] (a) Bieber, K., Hundt, J. E., Yu, X., Ehlers, M., Petersen, F., Karsten, C. M., … & Ludwig, R. J. (2023). Autoimmune pre-disease. Autoimmunity Reviews, 22(2), 103236. (b) Xiao, Z. X., Miller, J. S., & Zheng, S. G. (2021). An updated advance of autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity Reviews, 20(2), 102743.

[36] (a) Tisoncik, J. R., Korth, M. J., Simmons, C. P., Farrar, J., Martin, T. R., & Katze, M. G. (2012). Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews, 76(1), 16-32. (b) Karki, R., & Kanneganti, T. D. (2021). The ‘cytokine storm’: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends in immunology, 42(8), 681-705.

[37] Hulten, L. M., Holmström, M., & Soussi, B. (1999). Harmful singlet oxygen can be helpful. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 27(11), 1203-1207.

[38] (a) Leisinger, U., Rüfenacht, K., Fischer, B., Pesaro, M., Spengler, A., Zehnder, A. J., & Eggen, R. I. (2001). The glutathione peroxidase homologous gene from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is transcriptionally up-regulated by singlet oxygen. Plant molecular biology, 46(4), 395-408. (b) op den Camp, R. G., Przybyla, D., Ochsenbein, C., Laloi, C., Kim, C., Danon, A., … & Apel, K. (2003). Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell, 15(10), 2320-2332.

[39] Devasagayam, T., & Kamat, J. P. (2002). Biological significance of singlet oxygen.

[40] Fridovich, I. (2013). Oxygen: how do we stand it?. Medical Principles and Practice, 22(2), 131-137.

[41] Davies, K. J. (2000). Oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and damage removal, repair, and replacement systems. IUBMB life, 50(4‐5), 279-289.

[42] (a) Evren, E., Ringqvist, E., Tripathi, K. P., Sleiers, N., Rives, I. C., Alisjahbana, A., … & Willinger, T. (2021). Distinct developmental pathways from blood monocytes generate human lung macrophage diversity. Immunity, 54(2), 259-275. (b) Tan, S. Y., & Krasnow, M. A. (2016). Developmental origin of lung macrophage diversity. Development, 143(8), 1318-1327.

[43] Chinnery, H. R., McMenamin, P. G., & Dando, S. J. (2017). Macrophage physiology in the eye. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, 469, 501-515.

[44] Puttur, F., Gregory, L. G., & Lloyd, C. M. (2019). Airway macrophages as the guardians of tissue repair in the lung. Immunology and cell biology, 97(3), 246-257.

[45] Rahman, I., & Adcock, I. M. (2006). Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. European respiratory journal, 28(1), 219-242.

[46] Arora, S., Dev, K., Agarwal, B., Das, P., & Syed, M. A. (2018). Macrophages: Their role, activation and polarization in pulmonary diseases. Immunobiology, 223(4-5), 383-396.

[47] Ogura, M., & Kitamura, M. (1998). Oxidant stress incites spreading of macrophages via extracellular signal-regulated kinases and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Immunology, 161(7), 3569-3574.

[48] Reichard, A., Wanner, N., Farha, S., & Asosingh, K. (2023). Hematopoietic stem cells and extramedullary hematopoiesis in the lungs. Cytometry Part A, 103(12), 967-977.

[49] (a) Bryndin, E., & Bryndina, I. (2020). Self healing of healthy condition at cellular level. Medical Case Reports and Reviews, 3, 1-4. (b) Adam, K., & Oswald, I. (1984). Sleep helps healing. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.), 289(6456), 1400.

[50] Atrooz, F., & Salim, S. (2020). Sleep deprivation, oxidative stress and inflammation. Advances in protein chemistry and structural biology, 119, 309-336.

[51] (a) Reimund, E. (1994). The free radical flux theory of sleep. Medical hypotheses, 43(4), 231-233. (b) Villafuerte, G., Miguel-Puga, A., Murillo Rodríguez, E., Machado, S., Manjarrez, E., & Arias-Carrión, O. (2015). Sleep deprivation and oxidative stress in animal models: a systematic review. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2015(1), 234952.

[52] (a) Solanki, N., Atrooz, F., Asghar, S., & Salim, S. (2016). Tempol protects sleep-deprivation induced behavioral deficits in aggressive male long–evans rats. Neuroscience letters, 612, 245-250. (b)

[53] Patki, G., Solanki, N., Atrooz, F., Allam, F., & Salim, S. (2013). Depression, anxiety-like behavior and memory impairment are associated with increased oxidative stress and inflammation in a rat model of social stress. Brain research, 1539, 73-86.

[54] (a) Garbarino, S., Lanteri, P., Bragazzi, N. L., Magnavita, N., & Scoditti, E. (2021). Role of sleep deprivation in immune-related disease risk and outcomes. Communications biology, 4(1), 1304. (b) Tobaldini, E., Costantino, G., Solbiati, M., Cogliati, C., Kara, T., Nobili, L., & Montano, N. (2017). Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 74, 321-329.

[55] Wilking, M., Ndiaye, M., Mukhtar, H., & Ahmad, N. (2013). Circadian rhythm connections to oxidative stress: implications for human health. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 19(2), 192-208.

[56] Besedovsky, L., Lange, T., & Haack, M. (2019). The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiological reviews.

[57] Mattson, M. P. (2008). Hormesis defined. Ageing research reviews, 7(1), 1-7.

[58] (a) Deary, V., Ellis, J. G., Wilson, J. A., Coulter, C., & Barclay, N. L. (2014). Simple snoring: not quite so simple after all?. Sleep medicine reviews, 18(6), 453-462. (b) Sarkis, L. M., Jones, A. C., Ng, A., Pantin, C., Appleton, S. L., & MacKay, S. G. (2023). Australasian Sleep Association position statement on consensus and evidence based treatment for primary snoring. Respirology, 28(2), 110-119.

[59] Gonzalez-Rothi, E. J., Lee, K. Z., Dale, E. A., Reier, P. J., Mitchell, G. S., & Fuller, D. D. (2015). Intermittent hypoxia and neurorehabilitation. Journal of applied physiology, 119(12), 1455-1465.

[60] Whitsett, J. A., & Alenghat, T. (2015). Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity. Nature immunology, 16(1), 27-35.

[61] Voynow, J. A., & Rubin, B. K. (2009). Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest, 135(2), 505-512.

[62] Gordon, B. R. (2008). Asthma history and presentation. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 41(2), 375-385.

[63] Burgel, P. R. (2012). Chronic cough and sputum production: a clinical COPD phenotype?. European Respiratory Journal, 40(1), 4-6.

[64] Diehr, P., Wood, R. W., Bushyhead, J., Krueger, L., Wolcott, B., & Tompkins, R. K. (1984). Prediction of pneumonia in outpatients with acute cough—a statistical approach. Journal of chronic diseases, 37(3), 215-225.

[65] Tollerud, D. J., O’connor, G. T., Sparrow, D., & Weiss, S. T. (1991). Asthma, hay fever, and phlegm production associated with distinct patterns of allergy skin test reactivity, eosinophilia, and serum IgE levels. The Normative Aging Study. Am Rev Respir Dis, 144(4), 776-81.

[66] (a) Pitts, T., Bolser, D., Rosenbek, J., Troche, M., & Sapienza, C. (2008). Voluntary cough production and swallow dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia, 23, 297-301. (b) Heijdra, Y. F., Pinto-Plata, V. M., Kenney, L. A., Rassulo, J., & Celli, B. R. (2002). Cough and phlegm are important predictors of health status in smokers without COPD. Chest, 121(5), 1427-1433. (c) Davies, D. (1974). Disability and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. British medical journal, 2(5920), 652. (d) Warren, C. P. (1979). Acute respiratory failure and tracheal obstruction in the elderly with benign goitres. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 121(2), 191.

[67] Heijdra, Y. F., Pinto-Plata, V. M., Kenney, L. A., Rassulo, J., & Celli, B. R. (2002). Cough and phlegm are important predictors of health status in smokers without COPD. Chest, 121(5), 1427-1433.

[68] (a) Biswas, S. K., & Rahman, I. (2009). Environmental toxicity, redox signaling and lung inflammation: the role of glutathione. Molecular aspects of medicine, 30(1-2), 60-76. (b) Shao, M. X., & Nadel, J. A. (2005). Dual oxidase 1-dependent MUC5AC mucin expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(3), 767-772.

[69] Price, M. E., & Sisson, J. H. (2019). Redox regulation of motile cilia in airway disease. Redox Biology, 27, 101146.

[70] World Health Organization. (2023). Accelerating anaemia reduction: Acomprehensive framework for action. World Health Organization.

[71] Wang, J., & Pantopoulos, K. (2011). Regulation of cellular iron metabolism. Biochemical Journal, 434(3), 365-381.

[72] Shaw, P., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2020). Nrf2–ARE signaling in cellular protection: Mechanism of action and the regulatory mechanisms. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 235(4), 3119-3130.

[73] Dewhirst, M. W. (2009). Relationships between cycling hypoxia, HIF-1, angiogenesis and oxidative stress. Radiation research, 172(6), 653-665.

[74] ORINO, K., LEHMAN, L., TSUJI, Y., AYAKI, H., TORTI, S. V., & TORTI, F. M. (2001). Ferritin and the response to oxidative stress. Biochemical Journal, 357(1), 241-247.

[75] Kensler, T. W., Wakabayashi, N., & Biswal, S. (2007). Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 47(1), 89-116.

[76] Li, N., & Karin, M. (1999). Is NF‐κB the sensor of oxidative stress?. The FASEB Journal, 13(10), 1137-1143.

[77] Clavo, B., Rodríguez-Esparragón, F., Rodríguez-Abreu, D., Martínez-Sánchez, G., Llontop, P., Aguiar-Bujanda, D., … & Santana-Rodríguez, N. (2019). Modulation of oxidative stress by ozone therapy in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced toxicity: review and prospects. Antioxidants, 8(12), 588.

[78] Sano, M., & Fukuda, K. (2008). Activation of mitochondrial biogenesis by hormesis. Circulation research, 103(11), 1191-1193.

[79] Sockrider, M., & Fussner, L. (2020). What is asthma?. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 202(9), P25-P26.

[80] Venkatesan, P. (2023). 2023 GINA report for asthma. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 11(7), 589.

[81] To be published

[82] Adeloye, D., Song, P., Zhu, Y., Campbell, H., Sheikh, A., & Rudan, I. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10(5), 447-458.

[83] Duan, K. I., Birger, M., Au, D. H., Spece, L. J., Feemster, L. C., & Dieleman, J. L. (2023). Health Care Spending on Respiratory Diseases in the United States, 1996–2016. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 207(2), 183-192.

[84] Paulson, K. R., Kamath, A. M., Alam, T., Bienhoff, K., Abady, G. G., Abbas, J., … & Chanie, W. F. (2021). Global, regional, and national progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 for neonatal and child health: all-cause and cause-specific mortality findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 398(10303), 870-905.

[85] Zhang, M., Wang, J., Liu, R., Wang, Q., Qin, S., Chen, Y., & Li, W. (2024). The role of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway in the treatment of respiratory diseases and the research progress on targeted drugs. Heliyon.

[86] (a) Barnes, P. J. (2008). The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of clinical investigation, 118(11), 3546-3556. (b) Xu, W., Zhao, T., & Xiao, H. (2020). The implication of oxidative stress and AMPK-Nrf2 antioxidative signaling in pneumonia pathogenesis. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 400.

[87] Kume, H., Yamada, R., Sato, Y., & Togawa, R. (2023). Airway smooth muscle regulated by oxidative stress in COPD. Antioxidants, 12(1), 142.

[88] Hashimoto, M., Tanaka, H., & Abe, S. (2005). Quantitative analysis of bronchial wall vascularity in the medium and small airways of patients with asthma and COPD. Chest, 127(3), 965-972.

[89] Michaeloudes, C., Abubakar-Waziri, H., Lakhdar, R., Raby, K., Dixey, P., Adcock, I. M., … & Chung, K. F. (2022). Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress in asthma. Molecular aspects of medicine, 85, 101026.